sierra-barter.com – The presidency of Andrew Johnson was one of the most contentious and pivotal in American history. As the 17th president, Johnson inherited the daunting task of rebuilding a nation shattered by the Civil War. His leadership during Reconstruction, the process of reintegrating the Southern states back into the Union and determining the status of newly freed African Americans, remains one of the most controversial aspects of his legacy. Johnson’s policies and his contentious relationship with Congress fundamentally shaped the course of Reconstruction and had a lasting impact on the nation’s racial and political landscape.

This article examines Andrew Johnson’s approach to Reconstruction, the political battles that defined his presidency, and the profound effects of his leadership on the future of the United States.

The Legacy of the Civil War and Lincoln’s Assassination

The End of the Civil War

By the time of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, the Union had won the Civil War, but the Southern states were left in ruins. The war had decimated much of the South’s infrastructure, economy, and social structure. The question of how to bring the Southern states back into the Union, and whether or not they should be punished for their rebellion, was a central issue facing the nation in the post-war period.

While Lincoln’s assassination had dealt a fatal blow to the hopes of a peaceful and conciliatory Reconstruction, his vision for reuniting the nation with compassion and leniency still loomed large. Johnson, who had been a Democrat and a Southerner, was seen as a possible bridge between the North and South. Despite his political background, he had remained loyal to the Union during the war, and Lincoln appointed him as vice president in part to appeal to Southern Unionists. With Lincoln gone, Johnson inherited a fractured nation and the enormous responsibility of leading the Union through the painful process of rebuilding.

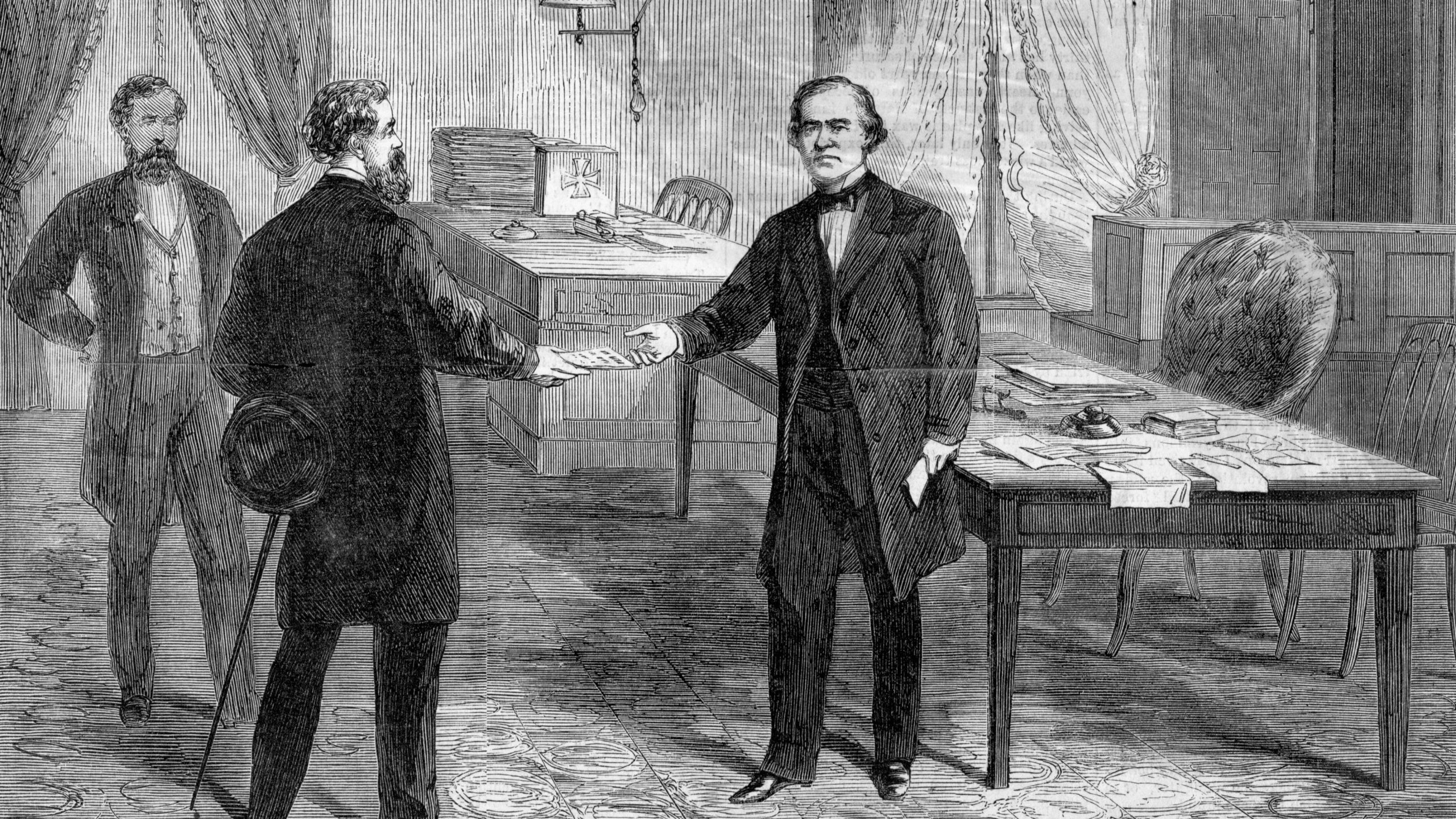

Johnson’s Accession to the Presidency

Following Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson took office as the 17th president on April 15, 1865. At the time, the nation was still reeling from the assassination, and the wounds of the Civil War had yet to heal. Johnson’s leadership was crucial in determining the course of Reconstruction. He faced immense pressure from both the Northern and Southern factions to lead the country through this turbulent period, and his decisions would leave a lasting mark on the nation.

Though Johnson was a Southern Democrat, he had remained loyal to the Union throughout the war and had been a staunch opponent of the secessionist movement. He had been the military governor of Tennessee, a state that had seceded but was later recaptured by Union forces. This experience gave Johnson credibility among Northerners, especially the Republicans, who held a majority in Congress. However, Johnson’s presidency was defined by his failure to understand the deep divisions that existed between the Northern and Southern factions, and his inability to reconcile his own Southern background with the demands of the post-war period.

Johnson’s Vision for Reconstruction

A Lenient Approach to the South

From the outset of his presidency, Johnson favored a lenient and rapid reintegration of the Southern states into the Union. Johnson’s vision for Reconstruction differed significantly from that of the Radical Republicans in Congress, who believed that a more rigorous and transformative approach was necessary to ensure the rights of freed slaves and prevent the reassertion of Southern power.

Johnson’s primary goal was to restore the Southern states as quickly as possible, with minimal federal interference. In his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction issued in May 1865, Johnson offered a pardon to most white Southerners who took an oath of loyalty to the Union. It allowed Southern states to hold constitutional conventions to re-establish their governments without significant input from African Americans. Johnson believed that by granting amnesty and pardons to former Confederate officials and soldiers, the South would reintegrate smoothly into the Union.

Johnson’s vision did not include protections for African Americans, and he opposed any measure that would grant them full political and civil rights. He also refused to endorse the idea of land redistribution, which would have provided freed slaves with economic opportunities. As a result, his policies were deeply disappointing to the growing faction of Radical Republicans who were committed to securing full civil rights for African Americans and transforming the Southern social order.

The Rise of the Black Codes

The swift return of former Confederate leaders to power in the South resulted in the passage of Black Codes—laws designed to restrict the freedom of African Americans and maintain a system of racial control. These laws varied from state to state but generally sought to limit the rights of African Americans, especially in terms of employment, mobility, and civil participation.

In Mississippi, for example, the Black Code required African Americans to sign labor contracts with white employers or risk being arrested for vagrancy. Other states passed similar laws that denied African Americans the right to vote, hold office, or serve on juries. The Black Codes were a direct challenge to the newly established 13th Amendment, which had abolished slavery, and they reflected the South’s reluctance to embrace racial equality.

The Black Codes angered Radical Republicans in Congress, who viewed them as a blatant attempt to restore the pre-war racial hierarchy. They believed that the federal government needed to intervene to ensure that African Americans were granted full citizenship and equal protection under the law.

Congressional Pushback

By 1866, Johnson’s lenient approach to the South and his failure to address the rights of African Americans had led to growing dissatisfaction in Congress. Radical Republicans began to push back against Johnson’s Reconstruction policies, arguing that the Southern states needed to be subjected to greater scrutiny and that civil rights protections for African Americans were essential to the future of the Union.

In response to the Black Codes and the general lack of progress in the South, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which sought to define and protect the civil rights of African Americans. The act was intended to nullify the Black Codes and guarantee equal protection under the law for all citizens, regardless of race. Johnson, however, vetoed the bill, arguing that it would undermine the authority of the states and that the federal government had no business interfering with state laws.

Congress, in an unprecedented move, overrode Johnson’s veto—marking the first time in U.S. history that a presidential veto had been overturned on a significant piece of legislation. This moment set the stage for a growing conflict between Johnson and Congress, which culminated in the passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868, guaranteeing citizenship and equal protection for all people born in the United States, regardless of race.

The Battle Over the Reconstruction Acts

The Reconstruction Acts of 1867

The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 represented a major shift in the federal government’s approach to Reconstruction. Under these acts, the South was divided into five military districts, each of which was placed under military rule to oversee the establishment of new, more democratic state governments. The acts required Southern states to draft new constitutions that would guarantee the civil rights of African Americans, particularly the right to vote, and to ratify the 14th Amendment.

Johnson strongly opposed these measures, arguing that they were an overreach of federal power and that the Southern states should be allowed to rejoin the Union on their own terms. He vetoed the Reconstruction Acts, but once again, Congress overrode his veto.

The Tenure of Office Act and Impeachment

By 1868, the battle between Johnson and Congress had reached a boiling point. In an attempt to assert his power over the Reconstruction process, Johnson began to dismiss key officials who supported the Radical Reconstruction agenda. Most notably, he removed Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, who had been an ally of the Radicals. This move directly violated the Tenure of Office Act, which had been passed by Congress to limit the president’s ability to remove cabinet members without Senate approval.

In response, the House of Representatives voted to impeach Johnson in February 1868, charging him with violating the Tenure of Office Act. The Senate held a trial, and while Johnson was acquitted by a single vote, the impeachment process effectively crippled his presidency. His authority was severely diminished, and Radical Republicans gained the upper hand in shaping Reconstruction policy.

The Legacy of Andrew Johnson

The Long-Term Impact of Johnson’s Policies

Andrew Johnson’s presidency left a complicated legacy. His failure to fully embrace the civil rights of African Americans and his lenient approach to the South allowed many of the old Confederate leaders to regain political power. The resulting Jim Crow laws, segregation, and disenfranchisement of African Americans in the South would persist for nearly another century.

Johnson’s strained relationship with Congress, culminating in his impeachment, also set a precedent for the future of presidential power and Congressional oversight. The impeachment marked the first time a sitting president was impeached, and although Johnson was acquitted, it demonstrated the potential for conflict between the executive and legislative branches.

Reconstruction and Its Aftermath

Although Johnson’s vision for Reconstruction ultimately failed, his policies nevertheless set the stage for later advancements in civil rights. The Radical Republicans, despite their differences with Johnson, eventually succeeded in passing the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments—key pieces of legislation that reshaped the nation and extended civil rights to African Americans. However, the failure to fully implement these protections during Johnson’s presidency set the stage for the Jim Crow era in the South.

Conclusion

Andrew Johnson’s presidency was a turbulent and divisive period in American history. His approach to Reconstruction—marked by leniency toward the South and a lack of protection for African Americans—left the nation deeply divided. His conflict with Congress, culminating in his impeachment, set a significant precedent for the balance of power between the branches of government. While Johnson’s vision for Reconstruction failed to secure the civil rights of African Americans, his presidency played a crucial role in shaping the nation’s post-war trajectory and left a lasting impact on the future of the United States.